Of all the great Bridgwater firsts, the most inspiring, morally uplifting and mildly unexpected, was the claim to be the first town to petition against the evil transatlantic slave trade, referred to by some as the ‘Black Holocaust’ whereby some 12 million Africans were forcibly removed from their homes and compelled to work as slaves in the cotton fields of the Americas. So I researched it, and luckily it’s all true. I even found the date ….May 2nd 1785. So how did this all come about?

The Slave Trade reached its height in the 18th century at the same time as Britain was leading the world in terms of industrial revolutions and empire building. And the links between these factors were obvious.

Origins of the Slave Trade

Although it was the Portuguese Empire builders in the 15th century that had first got involved in the trading and exploitation of African Slaves, largely along the Gold Coast (Modern day Ghana) the other powers quickly also became involved and Britain was to play a major part. During the Elizabethan period it was the seafarer John Hawkins that led the way, setting up a slave trading syndicate of wealthy merchants and publishing a book “An Alliance to Raid for Slaves”.

And surprising as it may seem, the Royal Family were trailblazers in making a quick buck from the project.

Royal Assent

It was the ‘restored’ King Charles II and then his brother James II who were to found the ‘Royal Africa Company’ to ‘exploit’ the slave trade in Africa,backed by the use of the Royal Navy and Army in their stated quest for “Gold, silver, negroes and slaves” –

It was Bristol merchant ships that led the way in taking largely metal, copper and brass goods to Africa with produce made in the newly industrialised Avon valleys to pay for the slaves , the same ships that took brass to Africa then took slaves to America and then brought back sugar, tobacco and rum to England.

When in 1709 the industrial revolution was given a massive boost by Abraham Darby and his new ‘high quality iron’ Britain was so far out in front that the 18th century looked like a boom time for the now fabulously enriched ruling classes.

When in the 1720s Queen Square was built in Bristol it contained the offices of no less than 20 African merchants. And,controversially, it was these very people, once they had their feet under the fine tables of the ruling classes ,who were to invest in theatres, libraries and the genteel pastimes whilst at the same time 1000s of African slaves were packed into ships and sent into slavery

The most famous example is probably Edward Colston (1636-1721) whose prosperous merchant wealth was built on slavery. Colston, a Tory MP and Member of Royal Africa Company, now of course has one of Bristol’s top theatre venues named after him and a statue in the centre of the city. By the time of Colstons death Bristol merchants were responsible for enslaving 16,000 Africans a year. Britain led the world in the buying and selling of human beings and the rich partied.

Bridgwater’s Own Slave History

So how did Bridgwater get involved in all this? Well, violently. It was in fact 849 white men from the West Country, including Bridgwater, who, as a result of rising up against James II through the Monmouth rebellion and the battle of Sedgemoor in 1685 , were sentenced to transportation to the West Indies to become slaves to work alongside native Indians and a small number at the time of imported Africans cutting sugar. People from Bridgwater witnessed the horror and forced removals and brutality of the Slave Trade at first hand

Of course there are some people who say that Bridgwater, a struggling port, was losing out to the rapid growth of Bristol due to that cities embrace of the Slave Trade and that’s why the Town wanted to try to stop the practice. But the evidence shows a higher level of altruism and the fact that as bigger ports more accessible to the sea, such as Liverpool, embraced the trade, Bristol went into a decline anyway. Bridgwater -halfway up a difficult river -was never going to be in the running.

And Bridgwater is a famously radical town, always reflected in the politics of the Town Council, so the 18th Century was no exception. We’re also very fortunate that one of the most famous sons of the town, the artist, merchant and politician John Chubb, lived through this period and, fortunately, was instrumental in getting the petition up and running.

Bridgwater in the 1780s

By the mid 18th Century Bridgwater had recovered from the disasters of the 17th century civil wars and rebellions and was becoming a rich little market town with a bustling seaport and newly gentrified homes along Castle street, built on the site of the old Castle that had been destroyed after the civil war siege in 1645, and most importantly was a centre of non-conformist radicalism, with largely a Whig(Liberal) council in the town but a Tory (Tory) pair of MPs with a vote largely drawn from the countryside and the rich….remember the poor weren’t allowed to vote and a working class had yet to be created…but it was coming.

A couple of major events were turning the tide against the Slave Trade. Whilst the rich were justifying their evil money making in the name of religion….“Surely God ordained them for our use otherwise he would have sent some sign”…the radicals also used the same spiritual language to condemn the trade.

The National Picture

London, in the 18th century, probably had a black population of around 10,000. It was regarded as ‘fashionable’ to have a black servant, but in fact the legal situation was unclear and many were pressganged from the streets by slavers and sold into the trade. In 1772 a major court case brought by radical lawyers such as Granville Sharp supporting the black Briton James Somerset in his bid not to be sent to the West Indies and established a ruling by William Murray the Lord Mansfield, that set a precedent that slavery could not exist in England without an act of Parliament – and there hadn’t been one, so the Common Law precedent that “No man can have property in another” was upheld.

In 1774 the American war of Independence broke out and Britain was awash with arguments for and against liberation,self determination and imperialism, so that when in 1781 the case of the Zong broke out, another court battle loomed. The Zong was a British slave ship whereby the masters had simply thrown 133 of their black slaves overboard and attempted to claim the loss against their insurance policy as you might with jettisoned cargo. Sharp and his colleagues were again in court trying to prosecute the ship owners who of course were found not guilty.

The Quaker Petition

By 1783 the Quakers presented the first petition to Parliament with 273 names on it from their congregation calling for an end to the practice. The Quakers were world leaders in the fight against Slavery with the simple viewpoint “How can one man own another if all are created equal” . The Quaker petition was read by Sir Charles Wray Whig MP for Westminster. Lord North-spoke for the Tory Governmentt and praised the Quakers as ‘mild and humane’ but then tabled the petition saying it would be impossible to abolish the slave trade. However, many also saw Quakers as ‘troublemakers’ who refused to sign oaths and refused to participate directly in parliamentary activity and so it was no surprise that the petition made no headway. What was needed was people through their elected representatives to step up to the mark and make the case.

By 1783 the Quakers presented the first petition to Parliament with 273 names on it from their congregation calling for an end to the practice. The Quakers were world leaders in the fight against Slavery with the simple viewpoint “How can one man own another if all are created equal” . The Quaker petition was read by Sir Charles Wray Whig MP for Westminster. Lord North-spoke for the Tory Governmentt and praised the Quakers as ‘mild and humane’ but then tabled the petition saying it would be impossible to abolish the slave trade. However, many also saw Quakers as ‘troublemakers’ who refused to sign oaths and refused to participate directly in parliamentary activity and so it was no surprise that the petition made no headway. What was needed was people through their elected representatives to step up to the mark and make the case.

The Bridgwater Petition

In 1785 Bridgwater stepped up to the mark and on May 2nd submitted the first petition from any town in the country.

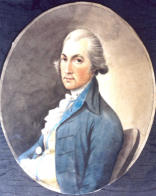

How did this come about? John Chubb (1746-1818) was a merchant and illustrator. Much of his work is available in the Blake Museum Bridgwater. He was particulary good at drawing 360 caricatures of the townspeople so if you have a family that dates back to that period, take a look and try to spot resemblances. He was a town councillor and crucially he was also a radical Whig and was in touch regularly with the National leader of the Whigs Charles James Fox , on occasion riding out to the Pipers Coaching Inn at Ashcott to secretly meet with him.

Fox was a major figure in British politics and was the rival to the Tory Government of Lord North that had fought so hard to suppress the American colonies. The war ended with a short lived coalition between the two only to be replaced by an interfering George III who appointed a new solely Tory administration under William Pitt (the Younger).

The 1780’s was a decade of turmoil which started with Britain recoiling from losing its American possessions and ended with the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789-which drew party lines even wider with Fox supporting and Pitt opposing.

Key Bridgwater Figures

Another key Bridgwater figure was George White , a local clergyman based at Huntspill, highly educated via Balliol College Oxford and ardent opponent of the Slave Trade. Yet another was Benjamin Allen, an influential merchant and Whig who had on a couple of occaisions even won the Parliamentary seat for his party from the Tories and his contributions were noted favourably by the Whig leader in his correspondence with John Chubb. In 1780 Allen lost the election but continued on the Borough Council as an active Whig. . Another prominent citizen was Robert Anstice (1757-1845) a ship owner, merchant and civil engineer becoming Somerset’s first County Surveyor, being particularly responsible for the Kings Sedgemoor Drain at Dunball and even drawing up plans for the future Durleigh Reservoir and who famously eloped to Gretna Green with local Quaker girl Susannah Ball.

Another key Bridgwater figure was George White , a local clergyman based at Huntspill, highly educated via Balliol College Oxford and ardent opponent of the Slave Trade. Yet another was Benjamin Allen, an influential merchant and Whig who had on a couple of occaisions even won the Parliamentary seat for his party from the Tories and his contributions were noted favourably by the Whig leader in his correspondence with John Chubb. In 1780 Allen lost the election but continued on the Borough Council as an active Whig. . Another prominent citizen was Robert Anstice (1757-1845) a ship owner, merchant and civil engineer becoming Somerset’s first County Surveyor, being particularly responsible for the Kings Sedgemoor Drain at Dunball and even drawing up plans for the future Durleigh Reservoir and who famously eloped to Gretna Green with local Quaker girl Susannah Ball.

But there were others on the Borough Council who’s family names still permeate the town to this day –Sealey, Gould, Giles, Marchand, Woolen, Phelps, Parsons and Baulch to name but a few.

The final piece of the jigsaw in this world where everything seemed to fall into place in one revolutionary year, was William Tuckett, who happened to be the Mayor of Bridgwater.

Tuckett had been a merchant in the Americas and had witnessed the Slave Trade at first hand and so it didn’t take much persuading by Chubb and White that him and his town could play a role in ending it.

They devised a petition which went exactly like this…

“The humble petition of the inhabitants of Bridgwater showeth, that your petitioners, reflecting with the deepest sensibility on the deplorable condition of that part of the human species, the African Negros, who by the most flagitious means are reduced to slavery and misery in the British colonies, beg leave to address this honourable house in their behalf, and to express a just abhorrence of a system of oppression, which no prospect of private gain, no consideration of public advantage, no plea of political expediency, can sufficiently justify or excuse. That, satisfied as your petitioners are that this inhuman system meets with the general execration of mankind, they flatter themselves the day is not far distant when it will be universally abolished. And they most ardently hope to see a British parliament, by the extinction of that sanguinary traffic, extend the blessings of liberty to millions beyond this realm, hold up to an enlightened world a glorious and merciful example, and stand foremost in the defence of the violated rights of human nature.”

The next problem was getting it to Parliament.

The Westminster Front

Bridgwater’s 2 MPs were rather non-interested Tories whose record in the house was largely one of absence. Alexander Hood (1726-1814) was a well respected Naval commander serving on various ships and in numerous wars including the Seven Years War and the American War of Independence but had been ‘given’ the role of MP for ‘something to do on his retirement’. In fact it didn’t last and he only stuck the role for a year speaking 4 times and only on naval matters before going back into service and continuing fighting in the French revolutionary wars and later being honoured as Lord Bridport.

The other MP was Anne Poulett. Born in 1711, Anne Poulett’s claim to fame was mainly that his family were such royalists they had named him after Queen Anne, never mind the gender issue.

Maybe he had something to prove…However, he died 2 months after the petition was presented at the age of 74 having represented Bridgwater for some 16 years. In fact the Poulett’s ancestral home was Hinton House (at Hinton St George- where there’s also a ‘Lord Poulett Arms’ pub to this day) and his ancestors had fought on the side of the King in the civil war Apart from presenting the painting “Descent from the Cross” (stolen from a Spanish Galleon) to St Mary’s church, his only claim to fame is that he presented the first anti slave trade petition. But it’s a good one.

Maybe he had something to prove…However, he died 2 months after the petition was presented at the age of 74 having represented Bridgwater for some 16 years. In fact the Poulett’s ancestral home was Hinton House (at Hinton St George- where there’s also a ‘Lord Poulett Arms’ pub to this day) and his ancestors had fought on the side of the King in the civil war Apart from presenting the painting “Descent from the Cross” (stolen from a Spanish Galleon) to St Mary’s church, his only claim to fame is that he presented the first anti slave trade petition. But it’s a good one.

But they did it. On May 2nd 1785 they presented it to Parliament….where it was ordered to “lie on the table”…which was parliamentary shorthand for “being politely ignored”. Poulett and Hood reported back “….there did not appear the least disposition to pay any further attention to it. Every one,almost, says that the abolition of the slave-trade must throw the West Indian islands into convulsions, and soon complete their utter ruin. Thus, they will not trust Providence for its protection in so pious an undertaking.”

For the Tory MPs , in fact, this was always going to be the case because most of them had some involvement in the Slave Trade one way or another. Their constituencies would ‘suffer’ if it ended….pretty much the same arguments we get today about everything from the nuclear to the defence industry…never mind the morality.

But Bridgwater had made its point, and it was apt that the first petition came from a town that exactly 100 years before had suffered the same fate as the Slaves they now showed solidarity with.

From Petition to Abolition

Another key visitor to Bridgwater at this time was Thomas Clarkson who was researching the evils of the slave trade and amassing evidence . Whilst visiting Bristol he was told he ought really to go down and see Bridgwater, which he did and met Chubb, Tuckett and White.

Clarkson recorded his visit to the town “Friday 20th Got on horseback at Six O’Clock, rode to Cross in Somersetshire. The Country is extremely beautiful, variegated by Hills & Valleys. About 12 or 13 miles from Bristol. There is a beautiful View on the right hand of the Bristol Channel & the Glamorganshire Hills – But the Day was rainy, and the Prospect in some measure prevented. I was almost wet through. Arrived at Cross which is 18 miles in two Hours & 10 at 8 o Clock. Got on Horseback at eleven – arrived at Bridgewater, which is 18 miles, a little after one – It rained a great Part of the Time. – The Country from Cross to Bridgewater is a low, flat, marshy Country – Dined at Bridgewater – In the Evening waited upon Alderman Sealy, and the Mayor Mr Crandon, who told me he had disposed of my Summaries to the Gentlemen of the Corporation; that he would call an Hall in a Fortnight for the Purpose, and that he had little Doubt of succeeding; at the same Time, he would endeavour to recommend the same Conduct to the Towns People in order that the Town of Bridgewater might be wholly unanimous”

He later went on to note “…called a meeting but found people already supported abolition”.

From 1785-1788 a further 183 petitions were sent to parliament, notably the Manchester Petition which had been signed by 10,639 – 20% of the entire city at the time. However, the Abolitionist still had to change this growing popular support into political change.

The publication of Clarksons pamphlet and then book “An essay on the slavery and commerce of the human species, particularly the African, translated from a Latin Dissertation” boosted the abolitionist campaign with the foundation of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787 and it’s prominent figure William Wilberforce, converted to the cause by Clarkson’s evidence ,leading the Parliamentary Campaign as an Independent MP and making his maiden speech in 1789.

An Abolition Bill was rejected by the Tory government in 1791 by 163 votes to 88 so a further 519 petitions containing over 390,000 signatures flooded Parliament.

In 1792 a bill was actually passed but only when amended to a ‘gradual’ ban (which meant ‘never’).

However, the fight against the slave trade is not just about the role of liberal white crusaders but also of rebellion and revolt by black people. There had been many uprisings but none more crucial than the Slave Revolt in Haiti in 1804 which showed the ‘gradual’ reformers that they couldn’t keep such an unjust system going indefinitely without the people taking matters into their own hands.

Finally it was Fox, on the collapse of the Pitt Government in 1806, who was able to introduce legislation to abolish the Slave Trade with the Slave Trade Act in 1807 (114 for and 15 against…we may need to ask Jacob Rees Mogg if he remembers their names).

Slavery Abolished

The Congress of Vienna, which concluded the Napoleonic wars in 1815, passed the motion declaring that “the Slave Trade desolated Africa, degraded Europe and afflicted humanity” and that it should be ended.

The USA Government passed an abolition bill in 1807 as well but it was to take a civil war in the 1860s to finally determine the freedom of African-Americans.

Meanwhile, back in Britain It was the radical reforming Government of the 1830s that introduced the Slavery Abolition Act (1833)….well, ‘radical reforming’ always ever only half true when Liberals are involved…so in fact the key part of the bill was ‘compensation to the slave owners’!! Good news for Church of England stalwarts such as the Bishop of Exeter who was compensated for owning 665 slaves

In 2006 British PM Tony Blair expressed his deep sorrow over the slave trade which he described as ‘profoundly shameful’ ….but offered no apology for fear that accepting liability would lead to reparations for the victims. Today, the prohibition on slavery and servitude is codified under Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights, incorporated into UK law by the Human Rights Act 1998 . Article 4 of the Convention also bans forced or compulsory labour. Let’s hope that this isn’t one of those awful European laws that the Brexiteers want removed……